By Lea Thin

From the early hype around ecotourism to today’s calls for decolonization – the way we talk about the downsides of travel has shifted remarkably. We analyzed the focus topics of our newsletter issues since 1999. Looking back at more than 25 years of TourismWatch newsletters shows: what started as a niche concern has become a central social and political issue.

The Early Years: Ecotourism as a Promise

When the very first TourismWatch bulletin came out in 1996, the mood around tourism was surprisingly upbeat. The buzzword of the day was “ecotourism” – and with it came the hope that travel could be more than just an engine for growth. It was supposed to help protect nature and support local communities. For many developing countries, ecotourism looked like a win-win: fighting poverty while protecting the environment. The peak of this optimism came in 2002, when the UN declared the “International Year of Ecotourism.” Yet while politics and the industry eagerly embraced the term, TourismWatch wasn’t convinced. As early as Issue 26 in 2002, it warned that sustainability might turn into nothing more than a marketing slogan. That caution proved prescient: today, greenwashing remains one of the industry’s biggest problems.

Human rights also entered the spotlight early. Already in 2003, Issue 31 reported on serious human rights violations linked to tourism activities. A year later, Issue 35 explicitly addressed the issue of sex tourism – at a time when most industry players remained silent. With this, TourismWatch took on a pioneering role, raising awareness of matters that only much later hit the global agenda.

New Realities: Digitalization and Overtourism

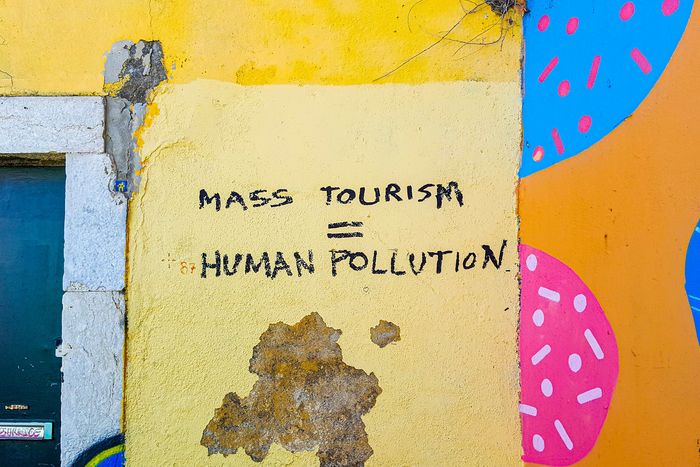

By the 2010s, the picture had changed completely. Tourism was booming, cities and beaches were overcrowded, and the term “overtourism” was born (Issue 90, 2018). The OECD defines a critical threshold as 930,000 tourists per square kilometer per year – a phenomenon that simply did not exist in the early 2000s.

This surge was driven above all by technology. Budget airlines made long-haul trips affordable, platforms such as Airbnb flooded local neighborhoods with visitors, and social media fueled the rush with picture-perfect destinations. What TourismWatch could hardly foresee in the early 2000s developed into one of the industry’s defining trends – the disruptive power of digitalization. Booking giants like booking.com reshaped the market, pushing out small players by algorithms while skimming their profits through hefty commissions. Online booking also enabled anonymity - a catalyst for sex tourism and child abuse in places with weak regulation.

Yet digitalization also has positive aspects: local providers can boost their visibility with just a few clicks on platforms like TripAdvisor, while automated processes such as online check-ins allow for more flexibility and family-friendly working hours.

From Analysis to Critique: Climate Justice and Decolonization

Back in the early 2000s, the environmental discussion in tourism focused mainly on cutting waste, saving water and protecting exotic wildlife. Today, the focus is on climate justice. In Issue 115 (2024), TourismWatch put it clearly: “Climate justice means reducing emissions, enforcing the polluter-pays principle, and enhancing the value of tourism at the destination level.“

The clash between ethical tourism and the “cheap deal” mentality had already been noted in 2004, but the idea really took off with the flight shame movement in Sweden (covered in Issue 98, 2019). Suddenly, the contradiction between global wanderlust and the climate crisis came into focus. The urge to travel stood in stark contrast to the guilt of a soaring CO₂ footprint. Flight behavior didn’t change much, yet the symbolic power of the debate has shifted the self-understanding of an entire industry.

The paradigm shift towards decolonization goes even deeper. While the focus initially lay on making tourism “softer,” today the system itself is being questioned. Ugandan scholar Maureen Ayikoru summed it up: Indigenous communities must no longer be passive “attractions” but must actively shape tourism in their homelands. The tourism industry, like culture and education, is now facing up to its long-suppressed legacy of colonial structures.

TourismWatch itself has also evolved – from a specialist newsletter into a platform for broader development education. With journalistic storytelling and sharp analysis, it has reached audiences far beyond experts, helping bring tourism critique out of the academic niche into mainstream debate.

Looking Ahead: From Tweaks to Transformation

Some issues remain stubbornly present: human rights violations such as child labor and sexual exploitation, the right to housing in cities squeezed by short-term rentals pushing up rents from Barcelona to Cape Town. But also new challenges emerged: the strains of overtourism, the disruptive power of digital platforms, and, most recently, artificial intelligence, which could both reshape and destabilize the sector. Geopolitical and ecological crises such as water scarcity are adding new tensions between locals and visitors. For example, TourismWatch reported from South Africa, where households were forced to limit water use while hotels and golf courses remained largely unaffected (Issue 119, 2025).

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) from 2015 still set the framework for sustainable tourism, with SDG 8 (“Decent Work”) highlighting the immense responsibility: today, one in ten jobs worldwide depends on tourism. Criticizing tourism is no longer a niche concern – it touches on central issues of our time: justice, climate, and participation.

This development reflects a broader societal shift: from optimizing existing systems to fundamentally questioning their legitimacy. What once was the hope of making tourism more sustainable through gentle adjustments has grown into the realization that profound changes in power and economic structures are necessary. Isolated projects without genuine participation have failed; what’s demanded is a fairer distribution of resources and power. For almost 30 years, TourismWatch has tracked and shaped these shifts. And this sharp, critical perspective will remain essential if tourism is to become not just more sustainable, but also fairer and future-proof.

TourismWatch newsletters have been digitized since 1999 and can be found in the archive on our website.